Sounds of Science?

On a presumably rainy, grey afternoon, they walked out onto a damp, soggy field. Feet squelching, stuck in mud. They entered a barn, let’s say, near that field. Inside, they chose, based on the “guidelines for the care and use of animals of the University of Florida,” the five “healthy, non-pregnant, grade Western ewes” from their flock. They looked them up and down. Maybe weighed them. The ewes were without food for 24 hours, anesthetized with halothane 2%, a drug administered hidden within oxygen, and used often for caesurean sections (despite not being recommended) – and then they were “killed with intravenous potassium chloride.” Potassium chloride is a drug used for lethal injections in the United States. It induces cardiac arrests. It sets fire to one’s veins all the way to the heart. Lights one on fire from the inside. They continued though. They shaved a segment of the abdomins of the ewes, and “the stomachs and intestines were delivered through a 20 cm incision in the upper right flank” as if they were babies and “flushed with water to remove pockets of gases and other products of digestion containing methane-producing organisms and replaced in the abdominal cavity.” Once everything was back in place, the ewes were then stitched back up. This is the preparation of ewes for a scientific experiment: to see whether or not low frequency sounds, or sounds of a vibroacoustic origin, have an impact on the foetus of pregnant women through an animal model, sheep.

They continued: “Ewes were suspended horizontally from a metal U-beam with heavy guage wire which was tunneled through tissue covering the spinal column. The ewe was then lifted to an upright position, carried out-of-doors, and the metal beam was placed 180 cm above ground on two spots.”

It is a disturbing image.

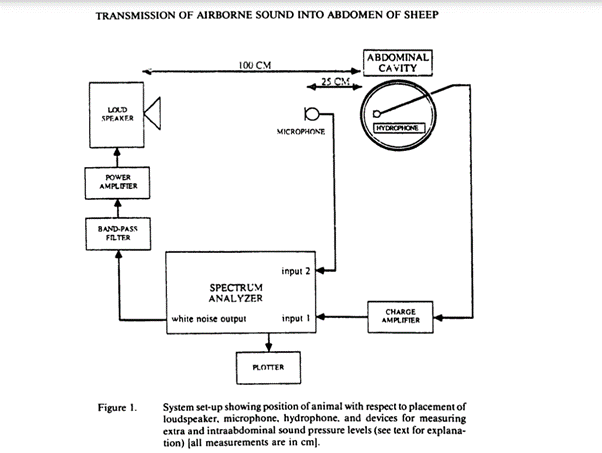

Then a miniature hydrophone (Model 8103, Bruel and Kjaer Instruments) was fitted inside the ewes on a “textite rod (0.5 x 100 cm)” through an incision on the high flank, and was then moved to a position within the abdominal cavity by massaging the outside of the ewe. It was calibrated with a pistonphone (Model 4223, Bruel and Kjaer). They filled the cavity with water to release some extra gas. The incision was then closed. About 1 m away from the ewes, a loudspeaker (Model HDH-2, Peavey Electronics Corp.) was placed. A broadband sound field was produced through the speaker, and the microphones inside of the ewes picked up whatever sounds passed through the flesh of the animal.

Everything was calibrated: The ewes, the phones, the speakers, the sounds.

Here is an appropriately abstracted diagram of the experiment:

The sounds of science – the tell-tales of the production of scientific facts. But it also reminded me of a famous description that begins Foucault’s Discipline and Punish:

This begs a question. What sort of legal code of pain (34), in Foucault’s words, is involved in the production of scientific knowledge, in the disciplining of objects under the scientific gaze (Lynch 1985), but also, here, caught within the listening practices of these scientists? What, moreover, is the role of “animal models” for mimicking the impact of infrasound or low frequency noise on the human body?

There is a lot that we do not know about low frequency noise and infranoise. Its effects on the human body, for instance. Is it a genotoxic agent? Do they carry disease? What about vibroacoustic diseases? Moreover, how do they complicate established forms of knowledge? How do they take shape within various ways of knowing (as audio recordings on Youtube? Description on forums? On noise maps? In bricoleured-measurement devices? In collective empirical enterprises? In government policy? Etc. etc.). How do they fit within policy? (urban planning and building regulations, e.g., are based on an A-weighted scale (according to standard human perception) and therefore does not take into account low frequency noise).

Infranoise and low frequency waves have been and are at the center of various scientific controversies, conspiracies, and mysteries.